By Berdymyrat Ovezmyradov and Yolbars Kepbanov, Researchers at Tebigy Kuwwat

Is it possible to quantify the global interest in Central Asian countries? Modern resources online allow such possibility. We would like to present some of our findings on based on books and online search. This post is based on an earlier published book chapter within the Central Asian Law project (Ovezmyradov and Kepbanov 2021).

We decided to measure Central Asian countries in terms of their online presence are based on the following tools made available by Google: Google Trends, Google Books and Ngram Viewer. Trending topics on the web are widely used to evaluate the popularity of certain topics (Althoff 2013). Google search trends reflect an interest in something. Google search engine was already used to forecast sales, travel, and confidence (Choi and Varian 2012). Meanwhile, Google Books is the repository for the human knowledge (Bergquist 2006, Michel 2011). The Ngram Viewer uses Google Books to calculate coverage of a searched term in published literature.

Google Trends shows search interest from the highest 100 points to 50 points (half as popular) to 0 (not enough data). This search interest (figures discussed below) is relative (not absolute). The Ngram Viewer shows percentages of how phrases occur in a large and structured set of texts (corpus) on Google Books.

We assume that Google search and Books can help measure the interest in Central Asian countries and their main ethnic groups. Google globally is a more popular search engine in most regions, though Yandex (particularly popular in the post-Soviet countries), Yahoo, and Baidu can be more popular in certain countries. We do not include social networks (i.e. Twitter and Facebook), video hosting (i.e. YouTube), and shopping (i.e. Amazon and AliExpress) due to their limitations in availability of data and relevance of results.

The following sections summarize results of the search with the aid of the aforementioned method. Our method is not very accurate but we believe it still can be used in the absence of readily available alternatives to measure such a comprehensive indicator as the global interest. Not all existing alternative names of a country (for instance, the Kyrgyz Republic) or an ethnic group was included in the further analysis for reasons of balance and space limits.

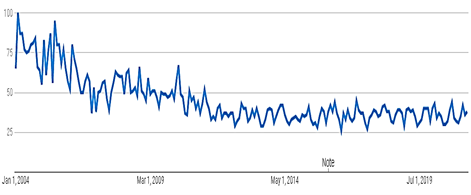

Interest in Central Asia declined in the 2010s relative to the 2000s (Figure 1).

Note: change in the data collection by Google in 2017.

Fig. 1 The interest in Central Asia over time, according to Google Trends (2021).

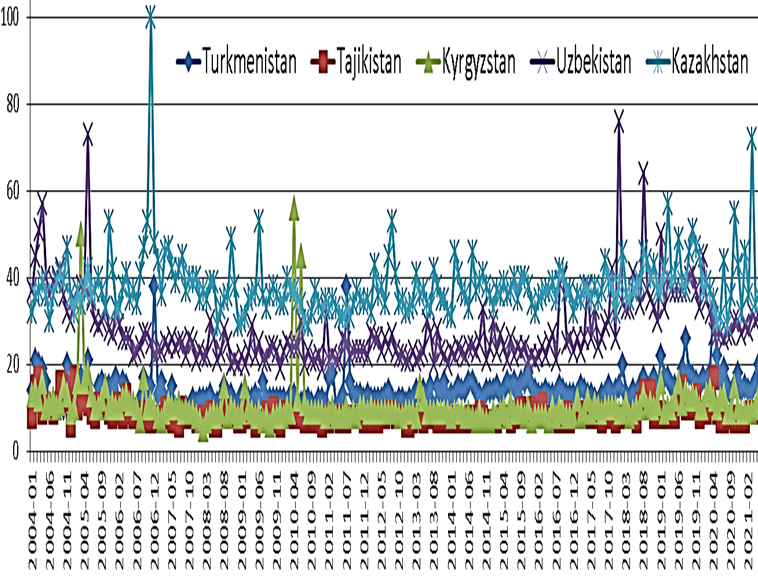

Kazakhstan was overall ranked highest among Central Asian countries on Google Trends, while Uzbekistan closed the gap after 2016 after the start of the liberalization reforms (Figure 2). Search interest in Turkmenistan was overall slightly higher compared to Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Interest in each country fluctuated with spikes often happening during dramatic changes in ruling elites (particularly in Kyrgyzstan).

Fig. 2 The interest in Central Asian countries over time, according to Google Trends (2021).

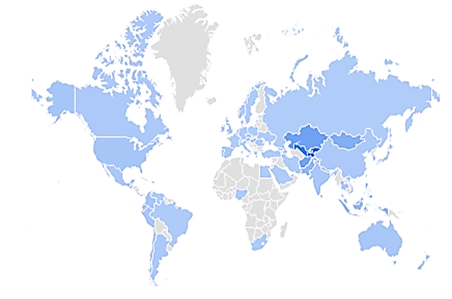

Interest in Central Asia appeared to originate mostly from within the region, neighboring countries, and the locations where substantial migration from the region took place (Figure 3).

Fig. 3 The interest in Central Asia by location according to Google Trends (2021).

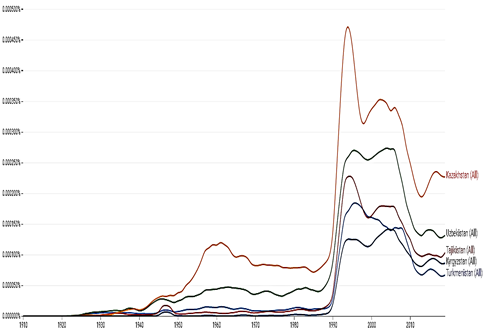

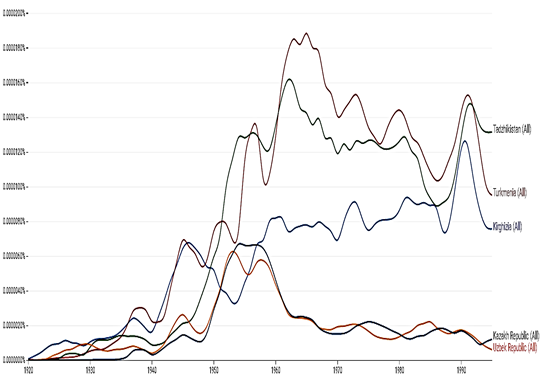

The share of mentioning Central Asian countries within Google Books over the past hundred years was uneven but with the trend of increasing share of publications written or translated within Central Asia in the English language (Figure 4). A notable increase was during a brief period of liberalization during so-called Khrushchev Thaw of the 1950s and 1960s after the Stalin era. In the early 1990s, another period of high coverage happened immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Declining interest after 2008 coincided with the global financial crisis and subsequent economic difficulties affecting the region. Kazakhstan was mentioned most frequently, followed by Uzbekistan. The recent trend of Central Asian countries mentioned relatively less by foreign books is not encouraging.

Fig. 4 The Central Asian countries in the English-language literature by the Ngram Viewer (2021).

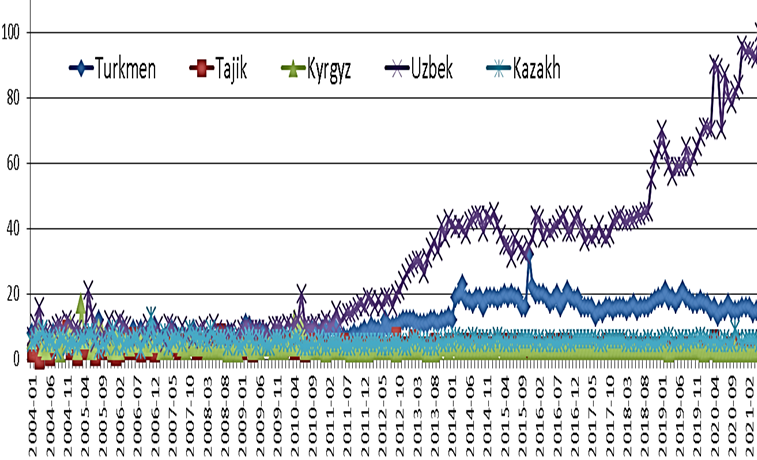

The five major ethnic groups of Central Asia are present all around the world, so national culture might be better represented by their adjectives than country names (Figure 5). The search terms below reflect either people or adjectives covered by books in foreign languages. The interest in Uzbek seemed much stronger compared to the country search term (Uzbekistan), with a more stable growth. Interest in Turkmen was second in online search since 2010, exceeding search trends for Kazakh, Tajik and Kyrgyz.

Fig. 5 The interest in the five ethnic groups of Central Asia according to Google Trends (2021).

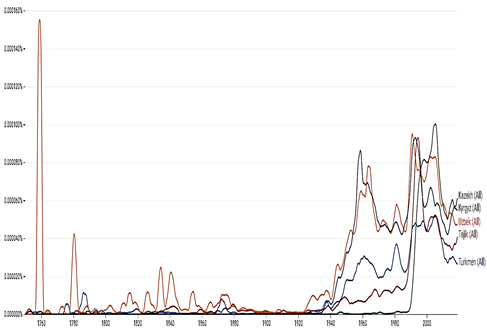

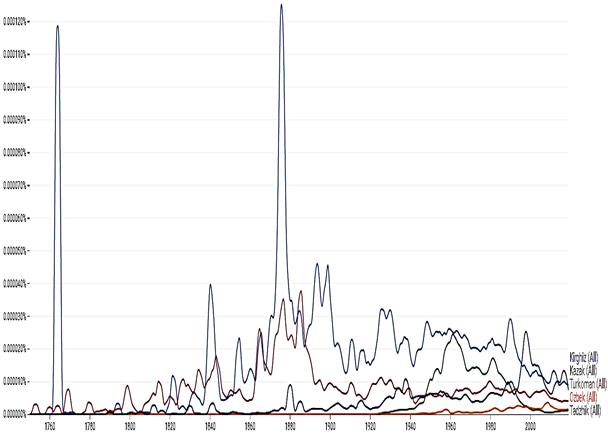

The earliest mentions of the five ethnic groups within documents in English on Google Books date back to the 1700s (Figure 6). The coverage of Central Asian countries was uneven for all the periods of publications. The figures provide relative or percentage share, not absolute values of interest. Furthermore, search in a foreign language cannot always precisely define a country or ethnic group because various terms might exist in different languages. Finally, there are errors in metadata on Google Books, though they are not widespread (for instance, books accidentally registered as published before the 19th century might actually belong to later periods). The comparisons here should be interpreted with caution due to the higher use of the alternative name for the countries (Kyrgyz or Kirghiz, for instance). There are admittedly more alternatives existing in both Russian and English languages not included in the comparisons due to their low frequency, but their inclusion could affect results.

The coverage of Central Asia in the literature remained low during the periods of expansion of the Russian Empire in the region. The mentions increased during the Soviet period, particularly the 1960s, but declined afterwards during the 1970s and 1980s. The mentions in the post-Soviet period first sharply increased during the 1990s and then declined during the 2010s. Relatively higher coverage of Uzbek in books during the earlier periods is obvious, though it is not as strong as in Google Trends. Kyrgyz had overall higher coverage in the recent decade, followed by Uzbek and Kazakh. Turkmen was initially mentioned more frequently during the Soviet period than Tajik or Kyrgyz but became lower in the ranking during the 2010s.

Fig. 6 The five ethnic groups of Central Asia in the English-language literature according to the Ngram Viewer (2021).

While search in the English language might better reflect the global interest in Central Asia, many users within the post-Soviet area prefer search in the Russian language.

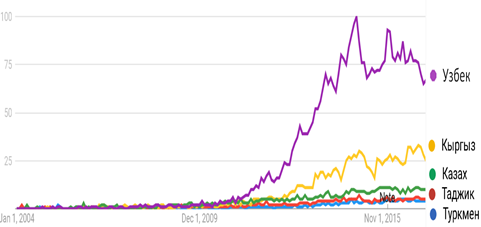

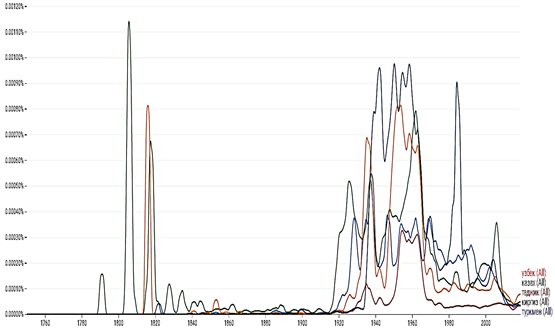

Online search in Russian names of the main ethnic groups in Central Asia thus should be analyzed separately (Figure 7). Similar to English-language literature, mentions of Uzbek were significantly higher, Kyrgyz was the second and Kazakh third. The overall interest in all the countries increased since 2009.

Fig. 7 The five ethnic groups of Central Asia in the Russian language according to Google Trends (2021).

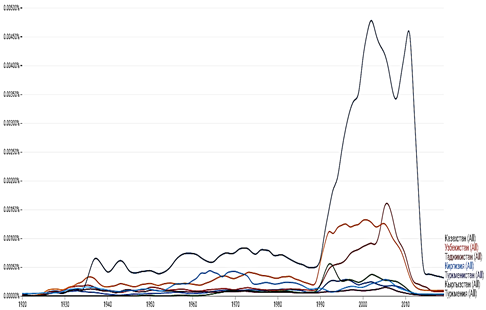

Unlike the earlier discussed results in the English language, Kazakhstan was the most frequently mentioned Central Asian country in the Russian language (Figure 8). Uzbekistan was the second position during most periods, followed by Tajikistan (especially in the coverage since 2000). The coverage of Turkmenistan and Kyrgyzstan could be higher if alternative names did not exist in Russian publication for each country. Transliteration in official documents is Turkmenistan (Туркменистан) and Kyrgyzstan (Кыргызстан), compared to Turkmenia (Туркмения) and Kirghizia (Киргизия) frequently used in less formal publications. Overall, recent publications in Russian media seemed slow to adopt the official names of the independent states with the continued use of habitual Soviet names.

The names of Central Asian states were subject of disputes. Kyrgyz Republic could be preferred by some people in the republic as the official name clearly emphasizing the ethnic character, while others could favor Kyrgyzstan as the name better representing all people in the country (Asanalieva (2015). There were suggestions in Kazakhstan at higher official level to change the country name eliminating the “-stan” ending due to the perception or possible confusion associated with similarly sounding country names using the suffix based on Persian root (Ford 2014).

Fig. 8 The Central Asian countries in the Russian-language literature according to the Ngram Viewer (2021).

Strong fluctuations in mentioning the ethnic groups in Russian-language literature are evident (Figure 9). Uzbek and Kyrgyz were frequently covered already in the earliest literature. All the five major Central Asian groups were better covered in books during the Soviet era compared to the period after gaining independence in 1991: the last time peak for Tajik was around 1960; and 1985 for Kazakh. Coverage of Kyrgyz increased later during 2000s.

Fig. 9 The five ethnic groups of Central Asia and related terms in the Russian-language literature according to the Ngram Viewer (2021).

Again, various alternative names in the English language were used to define the Central Asian countries and corresponding adjectives (Figures 10 and 11). Official country names involving the “republic” did not appear to be widespread. Less formal names such as Turkmenia, Tadzhikistan, and Kirghizia were frequent yet. Older adjectives and nouns, such as Turkoman and Kirghiz, were frequent within the earliest literature in English.

Fig. 10 The presence of alternative names of Central Asian countries in the English-language literature, according to the Ngram Viewer (2021).

Fig. 11 The presence of the alternative names of five ethnic groups of Central Asia and related terms in the English-language literature according to the Ngram Viewer (2021).

To summarize, Google search interest and coverage on Google Books can be used to measure the global interest in Central Asian countries and their main ethnic groups. After a peak in coverage during the 1990s and 2000s, there was a relative decline in interest as measured by online search and literature coverage in both English and Russian languages. Kazakhstan was frequently mentioned in the literature, while Uzbek related search terms seemed to attract relatively higher interest online. The analysis also showed the various names in English and Russian languages, some dating back to pre-Soviet times, still used in the literature. We would like to leave the deeper analysis of results and their implications for policymakers as directions of future work

References

Althoff, T., Borth, D., Hees, J., Dengel, A. (2013). Analysis and forecasting of trending topics in online media streams. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM international conference on Multimedia (pp. 907-916).

Asanalieva, D., Botoeva, A., Doolotkeldieva, A., Gullette, D., Heathershaw, J., Juraev, S., Spector, R. A. (2015). Kyrgyzstan beyond “democracy island” and “failing state”: Social and political changes in a post-Soviet society. Lexington Books.

Bergquist, K. (2006). Google project promotes public good. The University Record. University of Michigan.

Ford, M. (2014) Kazakhstan’s President Is Tired of His Country’s Name Ending in ‘Stan’. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/02/kazakhstans-president-is-tired-of-his-countrys-name-ending-in-stan/283676/ (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Google Books (2021) Ngram Viewer https://books.google.com/ngrams# (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Google Trends (2021) https://www.google.com/trends (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Michel, J. B., Shen, Y. K., Aiden, A. P., Veres, A., Gray, M. K., Pickett, J. P., Aiden, E. L. (2011). Quantitative analysis of culture using millions of digitized books. science, 331(6014), 176-182.

Ovezmyradov, B., Kepbanov, Y. (2021). Human capital and liberalization in Central Asia: comparative perspectives on development (1991 – 2020). Lund University (Media-Tryck).