By Berdymyrat Ovezmyradov and Yolbars Kepbanov, Researchers at Tebigy Kuwwat

In this article, presence of Central Asian countries and their main languages online are presented separately on country domain and Wikipedia levels. It is a summary of a part of book chapter earlier published by the authors within the Central Asian Law project (Ovezmyradov and Kepbanov 2021).

Less known areas within the former Soviet Union, Central Asian countries are still not well known and recognized globally even after three decades of independence (Rossabi 2021). Governments in the region took efforts to promote digital transformation, perhaps recognizing they are still far behind in this respect many other countries (Chikoniya 2019). However, digital content creation received less attention than deserved in the process when users worldwide actively search information online. The problem of insufficient presence online has to be addressed as a key aspect of digitalization and even nation branding. The region lagged behind post-Soviet comparators in the content creation with a relatively low number of online resources and Wikipedia pages.

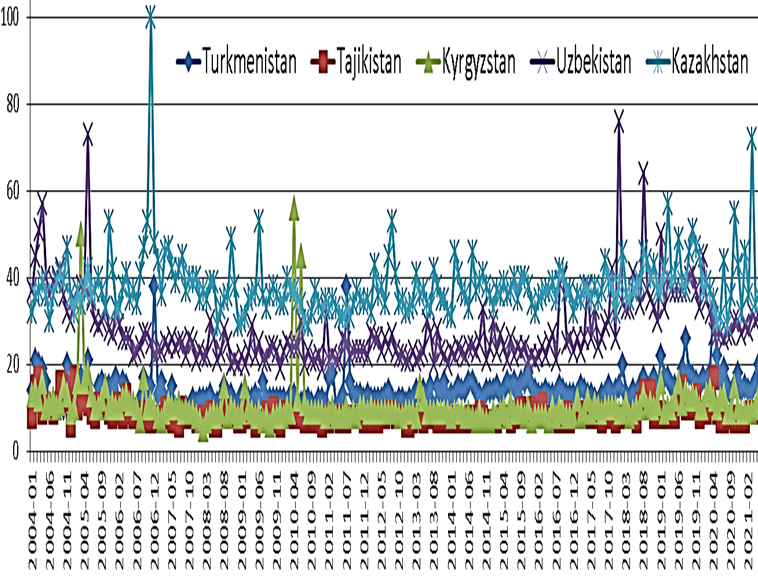

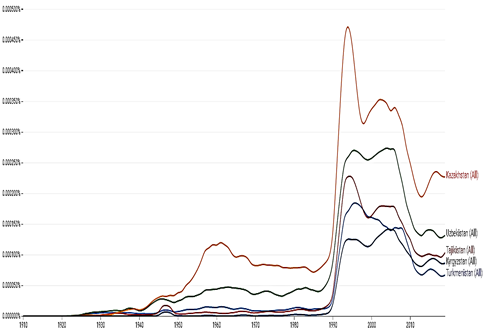

How well are Central Asian countries represented in the most popular sources of information online? Google and Wikimedia Foundation have data to help quickly answer this question. The online presence in those crucial sources of information worldwide can serve as an indirect indicator despite its limitations. Though imperfect, the creation and popularity of online materials can approximately reflect the of digitalization level in at least some aspects. Digitalization is a general term for the way social life is restructured around digital communication and media (Bloomberg 2018). Officially declaring importance and support for digitalization, Central Asian countries had the further widening digital gap (Chikoniya 2019). Central Asia experienced demonstrated relatively low growth in E-commerce and share of ICT services in exports (Erokhin 2020). Kazakhstan became a Central Asian leader in digital transformation (Erokhin 2020). The country was among the first in the region to attract the attention of the international audience (Stock 2009). Kazakhstan’s economy is relatively large and open compared to most Central Asian countries. It is therefore not surprising that the country managed to reach the greatest online interest and content creation.

To estimate the volume of online resources created within all post-Soviet countries, Google search results for “site:” term and the top-level internet code of a country domain was used. Table 1 presents the results. Kazakhstan was ahead other Central Asian countries but still lagged behind the post-Soviet countries out of the region when results are weighted by population or GDP size. Again, liberal democracies outside the region achieved impressive performance here relative to the size of their population and economy. This finding is relevant due to the growing importance of the digital economy and nation branding for all the newly independent states.

Table 1 Google search results in the post-Soviet domains.

| Country | Domain | Google search results |

| Russian Federation | .ru | 2 200 000 000 |

| Ukraine | .ua | 395 000 000 |

| Estonia | .ee | 256 000 000 |

| Lithuania | .lt | 157 000 000 |

| Belarus | .by | 103 000 000 |

| Kazakhstan | .kz | 88 700 000 |

| Latvia | .lv | 80 300 000 |

| Azerbaijan | .az | 37 900 000 |

| Uzbekistan | .uz | 31 300 000 |

| Armenia | .am | 28 600 000 |

| Georgia | .ge | 28 400 000 |

| Moldova | .md | 19 300 000 |

| Kyrgyzstan | .kg | 14 500 000 |

| Tajikistan | .tj | 6 220 000 |

| Turkmenistan | .tm | 3 530 000 |

Note: search results are approximate as of May 22, 2020.

Wikipedia is a popular source of information on many topics, with many users worldwide preferring it even to the various alternative information provided by organizations (Okoli et al 2014). The geolocated Wikipedia articles can be used for predicting a country’s socio-economic development, including health and education and other indicators of human capital (Sheehan et al 2019). Number of Wikipedia edits is among innovation indicators reflecting creativity levels in countries (Dutta and Lanvin 2013).

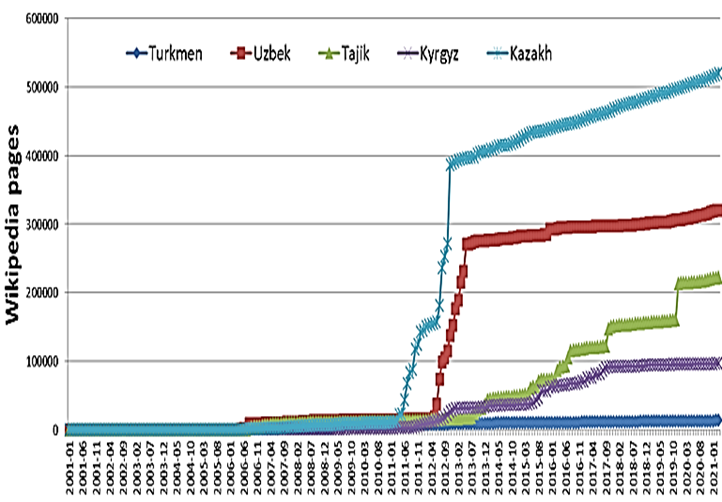

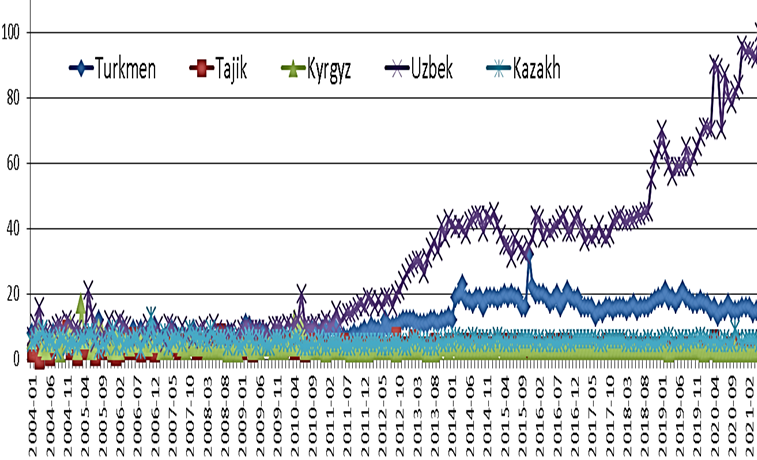

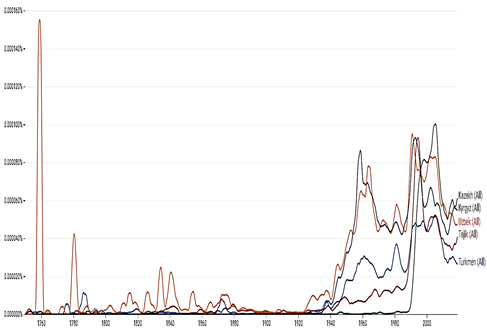

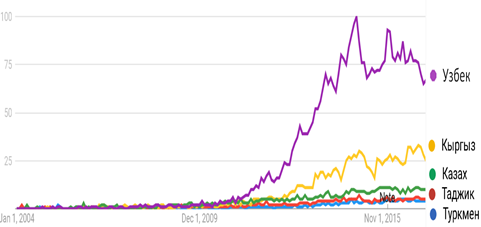

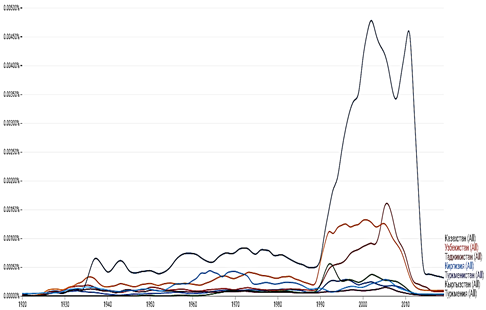

The volume of Wikipedia pages in the main Central Asian languages increased (Figure 1). Contributions in Kazakh and Uzbek languages visibly increased relative to Tajik and Kyrgyz languages in 2010s, while number of pages in Turkmen language remained the lowest in the region. Pages in Kazakh and Tajik seemed to grow in volume at the fastest pace since 2012.

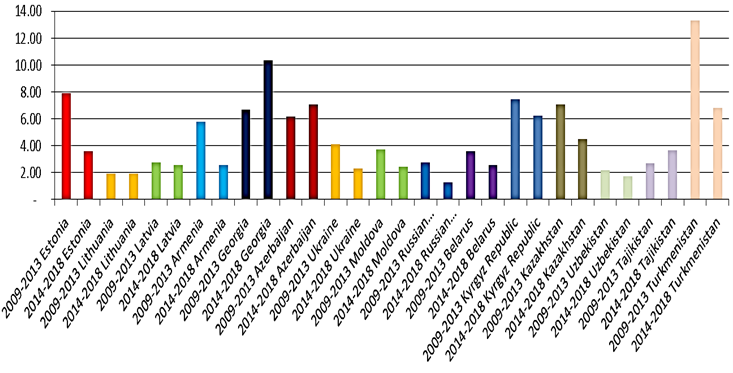

The total number of active users, pages, and media in the main languages of post-Soviet countries suggests many countries of comparable population size mostly outperform their Central Asian counterparts (Table 2). The relative performance appears to depend on the growth in liberalization and economy, in addition to population size. Kazakhstan’s national language had the highest Wikipedia indicators among Central Asian countries and was among the leaders within the entire post-Soviet comparisons. Kyrgyzstan achieved relatively high position in the region when weighted by its economy and population size. The comparisons on Wikipedia, again as in Google search results, still show the lower activity of Central Asian countries relative to the countries of similar population and economic size.

Table 2 Wikipedia contributors in the main languages of post-Soviet countries (Source: Wikimedia Commons 2021).

| Language | Articles | Admins | Active users | Images |

| Russian | 1 723 439 | 79 | 11 681 | 230 863 |

| Ukrainian | 1 091 925 | 45 | 3 460 | 111 098 |

| Armenian | 284 302 | 11 | 581 | 10 642 |

| Kazakh | 228 213 | 18 | 371 | 10 067 |

| Estonian | 219 204 | 33 | 737 | 726 |

| Belarusian | 204 599 | 10 | 284 | 3 340 |

| Lithuanian | 199 231 | 10 | 400 | 23 134 |

| Azerbaijani | 180 766 | 16 | 977 | 23 895 |

| Georgian | 152 727 | 4 | 301 | 14 760 |

| Uzbek | 140 329 | 11 | 239 | 1 670 |

| Latvian | 107 527 | 13 | 315 | 24 874 |

| Tajik | 103 193 | 6 | 79 | 463 |

| Kyrgyz | 80 763 | 2 | 72 | 2 688 |

| Turkmen | 5 916 | 1 | 45 | 319 |

Note: Language spoken in Moldova overlapping with Romanian.

So what can be done to close the gap in creating online resources? Governmental measures mostly limited to literacy, economic and technical aspects of the problem in the region evidently were not enough. Liberalization is an underestimated power in digitalization. Volume and quality of online content depend on the local talent and foreign influence. The progress in digital transformation of Central Asia should include loosening excessive government restrictions in the internet access, research, small business, and foreign investment. Human capital and institutions in Central Asia demonstrated lower performance compared to the majority of post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe on essential indicators of governance as prerequisites for knowledge-based economy (Veugelers 2011). Unfortunately, the recent progress in liberalization does not allow being very optimistic about prospects for the near future.

To summarize the article, the lack of digital content creation and online information overall has implications for digitalization and branding on the national level. Users of languages and domains of Central Asian countries created less online content indexed in Wikipedia (the top reference site) and Google (the top search site online) relative to post-Soviet countries when adjusting for the size of economy and population. More socio-political freedoms and fewer restrictions to access information online could undoubtedly help realizing the digital capacity in the region better than purely technical and economic incentives.

Key words: Central Asia, digitalization, internet, Google, Wikipedia.

References

Bloomberg, J. (2018) Digitization, Digitalization, And Digital Transformation: Confuse Them At Your Peril. Forbes https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonbloomberg/2018/04/29/digitization-digitalization-and-digital-transformation-confuse-them-at-your-peril/ (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Chikoniya (2019) The Digital Potential of the EDB Member Countries. Eurasian Development Bank.

Dutta, S., & Lanvin, B. (2016). The global innovation index 2013: the local dynamics of innovation.

Erokhin, D. (2020). Comparative Analysis of Digital Development in Central Asian Countries. OSCE Academy in Bishkek.

Okoli, C., Mehdi, M., Mesgari, M., Nielsen, F. Å., Lanamäki, A. (2014). Wikipedia in the eyes of its beholders: A systematic review of scholarly research on Wikipedia readers and readership. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(12), 2381-2403.

Ovezmyradov, B., Kepbanov, Y. (2021). Human capital and liberalization in Central Asia: comparative perspectives on development (1991 – 2020). Lund University (Media-Tryck).

Rossabi, M. (2021) Central Asia: A Historical Overview. Asia Society. https://asiasociety.org/central-asia-historical-overview (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Sheehan, E., Meng, C., Tan, M., Uzkent, B., Jean, N., Burke, M., Ermon, S. (2019). Predicting economic development using geolocated Wikipedia articles. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining (pp. 2698-2706).

Stock, F. (2009). The Borat Effect. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 5(3), 180-191.

Veugelers, R. (2011). Assessing the potential for knowledge-based development in the transition countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Society and Economy, 33(3), 475-504.

Wikimedia Foundation (2021) Wikimedia Statistics https://stats.wikimedia.org/#/all-projects (accessed on 20.05.2021).

Comments