In this post, Dr. Yolbars Kepbanov and Dr. Berdymyrat Ovezmyradov share results of a preliminary analysis on the regional state of non-hydro renewables.

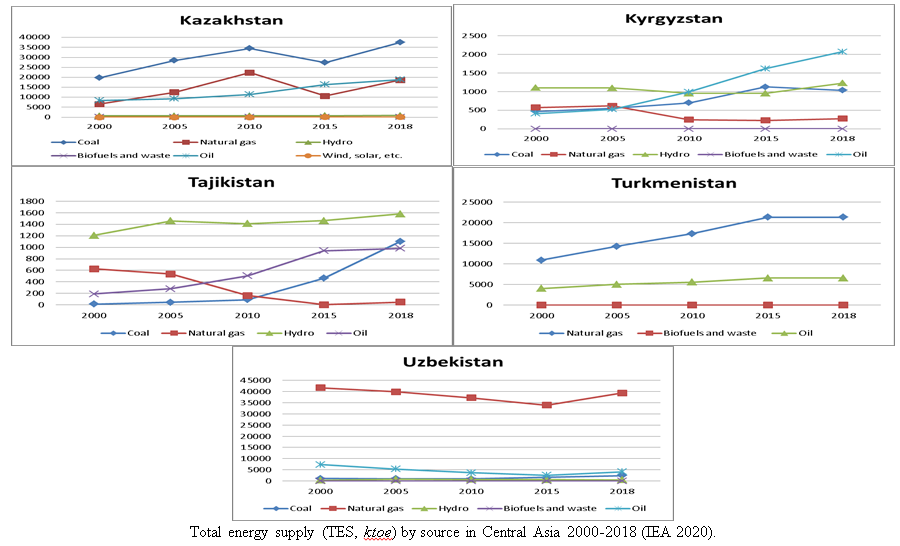

The decreasing cost of renewable energy from wind and solar is a technological development with broad implications for all Central Asian economies. The share of wind and solar energy in the region remained negligible for a long time due to the abundant supply of cheap energy from fossil or hydro resources. Central Asian countries remain heavily dependent on consumption, exports, or transit of fossil fuel. While there was obvious progress in renewables elsewhere in the post-Soviet area, Central Asia until recently has not shown adequate levels of interest in developing wind and solar power. Such approach could lead to loss of opportunities in reducing electricity costs and addressing sustainability issues. The countries and investors in the region can seize the opportunities for introducing a more sustainable energy mix during the major modernization and replacement of power generating capacity expected in the coming years.

Underutilized potential

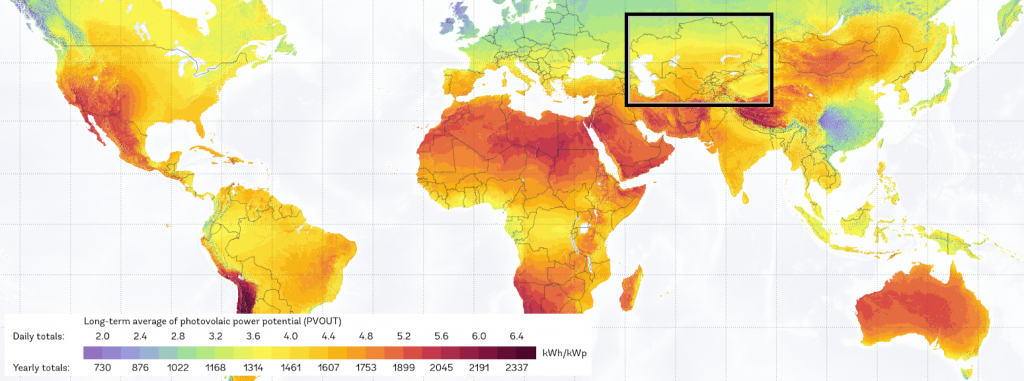

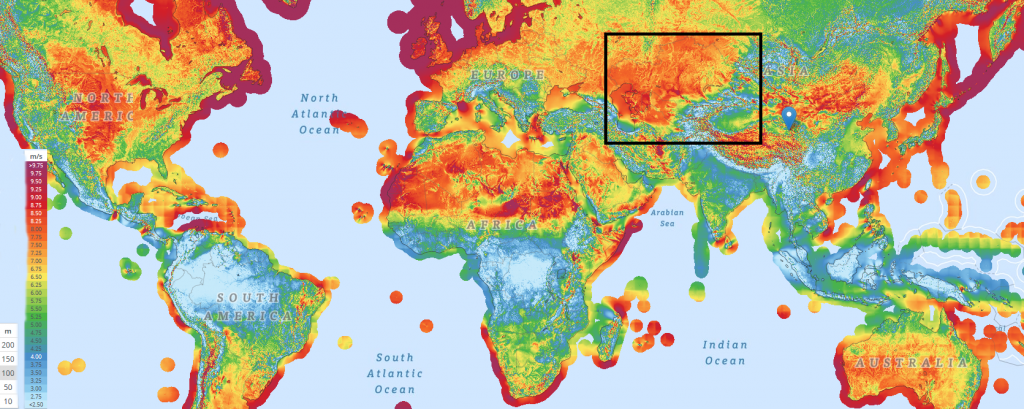

As the following figures illustrate, Central Asia has high potential for the generation of electricity from both onshore wind and sun relative to the larger parts of Eurasia. North-Western parts of Central Asia encompassing Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan in particular have a large potential for wind power. The larger part of Central Asia has a high number of sunny hours with close to annual 300 sunny days. This potential for a stable uninterrupted supply of solar power is particularly relevant for Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan – countries prone to seasonal or weather-related fluctuations in energy supply (EIU 2017). Wind and solar in Kazakhstan, solar and biogas in Uzbekistan, small hydropower in Kyrgyzstan, small hydropower and solar in Tajikistan, and solar in Turkmenistan have the higher prospects (Nabiyeva 2018). Floating solar technology tethered to the bottom of the reservoir or canal seems especially promising for Central Asia with its extensive network of irrigational channels and dams. The share of biomass in the regional energy mix is likely to remain low due to the inherent logistical challenges in collecting feedstock from vast areas.

Before 2020, Central Asian countries mostly limited non-hydro renewable actions to participation in conferences, exhibitions, declarations, and initial legislation (Marques 2018). Figure at the beginning of this post illustrates the negligible share of non-hydro renewables. Certain supporting measures (see the table) were taken, but there were few policies related to renewables in transport and heating/cooling sectors as of 2019 (REN21 Secretariat 2020). Kazakhstan seems to lead the region in new wind and solar developments (Marques 2018; Cohen 2020). But even in this leading country, the supply from installed non-hydro capacity below one percent was meager compared to the most countries in the world. Increasing interest toward renewables could also partially be motivated by the positive image and desire to follow global trends. There is even concern that the state interest in the renewables could lead to the showcase of projects that have weak relation to the real market needs (Nabiyeva 2018). Meanwhile, neighboring Russia and Ukraine implemented advanced cooperation, assessments, and large projects on a national scale. Ukraine that was traditionally reliant on hydrocarbon imports managed to increased the share of wind and solar in total energy supply almost 50-fold in the period 2010 to 2020 (IRENA 2020, IEA 2020).

Table 1: Targets and policies in Central Asian renewables as of 2019 (REN21 Secretariat 2020).

| Kazakhstan | Uzbekistan | Kyrgyzstan | Turkmenistan | Tajikistan | |

| Capacity targets | -Bio-power 15.05 MW at three stations by 2020 -Hydropower 539 MW at 41 stations by 2020 -Solar power 713.5 MW at 28 plants by 2020 -Wind power 1,787 MW at 34 stations by 2020 | -Solar PV 157.7 MW by 2019; 382.5 by 2020; 601.9 by 2021; 1.24 GW by 2025 -Wind power 102 MW by 2021; 302 MW by 2025 | Hydropower (small-scale) 100 MW by 2020 | ||

| Feed-in Electricity Policies | In 2013 | Date unknown | |||

| Tradable REC | Available | ||||

| Tendering | Available | Available | |||

| Investment or production tax credits | Available | ||||

| Public investment, loans, grants, capital subsidies or rebates | Available |

Why progress was slow

No precise studies were made on reasons for inadequate use of non-hydro renewables. The most obvious explanation is economic, technological, and political attractiveness of fossil fuel supported by its low cost, less variable output, and widespread subsidies in Central Asia (Nabiyeva 2020). Table 2 suggests consumers in Central Asia have access to the cheapest electricity in the world. And the actual cost for consumers could be even lower depending on the season, industry, market exchange rates, and quotas of nearly free electricity. Heavy government subsidies in the region undoubtedly play role distorting market prices in the region (IEA 2020). Even without the effect of subsidies, actual electricity costs based on fossil and hydro are still among the lowest in the world. In fact, so cheap is the cost of electricity ($0.01 to $0.03 per kWh from private power plants in Kazakhstan for foreign businesses) that bitcoin miners abroad considered moving to Central Asia (Redman 2020).

Table 2: Estimates of typical electricity prices in post-Soviet countries.

| Country | Electricity prices for business in 2019 (kWh, $) | Electricity prices for households in 2019 (kWh, $) |

| Turkmenistan | 0.010 | 0.007 |

| Tajikistan | no data | 0.015 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 0.020 | 0.010 |

| Uzbekistan | 0.030 | 0.015 |

| Kazakhstan | 0.050 | 0.040 |

| Azerbaijan | 0.050 | 0.040 |

| Georgia | 0.050 | 0.060 |

| Armenia | 0.070 | 0.080 |

| Ukraine | 0.080 | 0.050 |

| Russia | 0.080 | 0.060 |

| Moldova | 0.090 | 0.110 |

| Belarus | 0.090 | 0.080 |

| Estonia | 0.110 | 0.190 |

| Lithuania | 0.130 | 0.180 |

| Latvia | 0.150 | 0.190 |

* Sources: GlobalPetrolPrices.com for most countries; some estimates were based on alternative sources that could be outdated: Enerdata (2020) for Uzbekistan, Gassner (2017) for Kyrgyzstan, Energypedia (2020) for Tajikistan, and local survey for Turkmenistan.

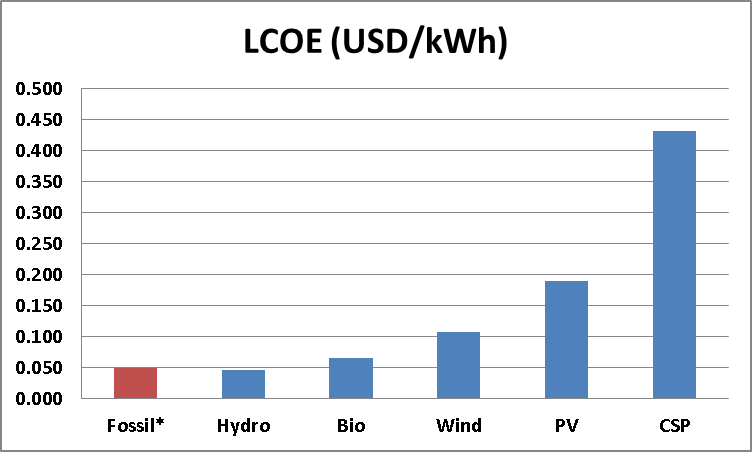

Central Asia is among the few remaining regions of the world where costs of traditional forms of energy are roughly equal or slightly lower compared to modern renewables (IRENA 2020). Meanwhile, the cost of fossil energy globally exceeds renewables for over half of recent projects (IRENA 2020). Furthermore, the estimate does not sufficiently take into account pollution, health, and other external costs of fossil. Given the ongoing decline of wind and solar costs, Central Asia cannot remain complacent with almost 100% reliance on fossil and hydropower. Prices that consumers pay in Central Asia for electricity appear below the cheapest objective measures such as LCOE using conservative estimates with cost difference of up to five times. The next figure shows comparisons of renewable cost in Central Asia based on assumption that fossil power is cheapest and non-hydro renewables are the most expensive in the region in 2019. Rather restrictive assumptions were made due to a shortage of specific project data on all Central Asian countries. However, they are further supported by the cost of existing projects in the region. For instance, the costs for solar residential systems up to 10 kW around 2018 were €1600-1800 in Kazakhstan – almost 50% more expensive than €1200-1300 in Germany. It was due to higher customs, transport, and guarantee costs relative to Europe (Nabiyeva 2018).

Note: costs assuming the low-cost range for fossil; the weighted average for mature renewables – hydro and bio; and 95th percentile for variable renewables – solar and wind.

Policymakers in Central Asia are aware of the fact that fossil energy in the region is not only cheaper but also less variable technology that requires lower storage relative to renewables. In addition to the low cost of fossil and heavy subsidies, logistical challenges, lack of expertise, financing limitations, inadequate linkage to currency, and opposition from the fossil industry lead to underutilized non-hydro renewables (Nabiyeva 2018). Furthermore, a conjecture can be made about other reasons such as lack of knowledge, conservative methods of costing, and lower priority of ecological problems that renewables could help solve.

Logistical challenges remain. Non-hydro renewables can still compete with fossil in limited areas. Rural, desert, and mountainous areas have underserved population in terms of energy supply. Those locations have abundant land available for renewable projects, but they often lack transmission and road infrastructure. Decentralized and autonomous solar systems that do not require transmission to remote areas could be suitable here, while wind turbine components are challenging to deliver and install in landlocked countries of Central Asia with underdeveloped infrastructure.

Lack of expertise

An issue that could hamper renewable development in Central Asia is insufficient knowledge and human resources. The region lagged behind most other areas of Eurasia in innovations and R&D output. In accounting for renewable costs, state agencies should switch to modern methods of costing projects using LCOE and other up to date techniques instead of obsolete methods that likely underestimate long-term costs of alternatives. Quantitative techniques such as SWITCH (capacity expansion model for the electricity sector) used by planners in other countries should aid decision-making in the future energy mix of the region.

The region has a history of renewable research. The reputed Sun Institute and Desert Institute within the Turkmen socialistic republic were established in Soviet-era. Experimental work on using solar and wind power for water purification in pastures within the desert was conducted since the 1970s. Such projects were limited in scale due to the high costs of solar and wind at that time. The priority of water desalination and energy supply for economy in remote areas with a decentralized network of combined solar-wind systems could become a starting point for the R&D in renewables in the region. Kazakhstan’s research and development could consider agricultural waste provided logistics, the big concern for biofuels, is cost-effective. Using cotton biomass is another perspective area for countries such as Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan where solid gin trash and on-farm cotton residues can be converted to energy. In addition to R&D, education systems of Central Asian countries would have to adapt, as they currently seem to offer little engineering and managerial training in all areas of non-hydro renewables. ADB supported launching the International Solar Energy Institute in Tashkent in 2012 (Nabiyeva 2018).

A long term solution to the issue of expertise and disadvantaged geographical location could be in local manufacturing of renewable components with direct foreign investments. This would spur the development of renewables in the region. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan with their current investment climate, scale, and resources of metals and machinery could be particularly attractive for manufacturing wind turbines. Still, all countries seem to have sufficient resources to supply energy and raw materials for manufacturing of cheap PV crystalline silicon modules for solar. The recent trend in renewable components is to move production to countries with lower costs (IRENA 2020). The Central Asian countries should provide better conditions for investors to gain the competitive advantage of hosting such manufacturing.

Foreign investment opportunities

USA, Japan, South Korea, India, neighbouring countries, and, in particular, China and countries of European Union (EU) could undoubtedly play important role in future development of non-hydro renewables in the region. Furthermore, institutional investors should be considered relevant.

China had a positive role in the development of renewables driving down costs and increasing expertise in manufacturing (The Economist 2020). Chinese companies could seem natural partners in developing renewables with their expertise and manufacturing prowess. About half of $575 billion promised under China’s Belt and Road Initiative as of 2019 is planned in energy projects, where Chinese companies such as State Grid (the world’s biggest utility) and Three Gorges will invest more in renewables abroad (The Economist 2020). State-backed Chinese investors could be considered among the first in large-scale projects by governments in Central Asia. At the same time, the governments should exercise caution in negotiating terms of agreements with Chinese businesses to avoid excessive dependence on single big partner, heavy debt burden, inadequate feasibility studies, and other difficulties that some developing countries involved in the massive Belt and Road Initiative already experienced.

Various organizations in the EU have expertise and resources to play a more active role in Central Asian renewables. European companies are highly competitive in renewables such as wind technology and sales on the global level. The European-level support has provided a market for Siemens Gamesa (the world’s top wind turbine manufacturers), Enel (the largest investor in wind and solar in developing countries), Orsted (world’s top developer of offshore wind-based in Denmark), Iberdrola (Spain), Electricité de France and Engie (France), and other global leaders in renewables (The Economist 2020). EU funding within Horizon Europe and other frameworks could greatly facilitate renewable developments.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB), the World Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and other influential institutional investors in Central Asian economies could contribute to the shift in the region to sustainable post-pandemic growth now that governments of the Central Asian countries face socio-economic uncertainty. EBRD, the largest institutional investor in Central Asia, prioritizes transition and promotion to green energy in Kazakstan and Uzbekistan. The World Bank Group Scaling Solar Program offers funding for the region. Implementation of renewables projects with high standards of social responsibility and sustainable growth would could achieve a win-win situation of getting much-needed investments but without compromising on sustainability goals for the populations of the countries and the international partners.

Conclusions

The world will undoubtedly continue efforts to reduce dependence on fossil fuel by expanding the share of wind and solar renewables. The commodity-exporting countries of Central Asia need to reassess the impact of non-hydro renewables. Coal, gas, and hydropower remained the major sources of energy in Central Asia. Unfortunately, the volume of coal-generated energy was expanding in the region. Many power plants in the region need replacement in the near future. This is the right time to better realize potential for non-hydro renewables that was not done previously due to economic reasons. Taken as a region, Central Asia has a high potential for onshore wind and sun. Not only will the expansion of renewables instead of fossil fuel capacity reduce the cost of energy mix; it will also have multiple benefits for ecology, emission targets, wider distribution, security, and resilience of electricity supply. The role of foreign partners is important for the development of renewables in Central Asia. Global investors should work with private and public sectors in the region to ensure high standards of transparency and sustainability. In particular, they could favour distributed low-cost solar that benefits individual consumers and small businesses in rural and other underprivileged areas. Legal and other support should be encouraged in international agreements to support vulnerable populations and other target beneficiaries with policies such as feed-in tariffs.

Sources

Cohen, A. (2020) Central Asia needs a financing solution to low oil prices. Forbes.

EIU (2017) Central Asia falling short of power generation potential. The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Enerdata (2020) Uzbekistan energy report. https://estore.enerdata.net/energy-market/uzbekistan-energy-report-and-data.html

Energydata.info (2020) Global Wind Atlas.

Energypedia (2020) Tajikistan Energy Situation. energypedia.info

Gassner, K. B., Rosenthal, N., Hankinson, D. J. (2017). Analysis of the Kyrgyz Republic’s Energy Sector. The World Bank.

GlobalPetrolPrices.com (2020) Electricity prices around the world. https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/electricity_prices/ (accessed on 20.09.2020).

IEA (2020) Countries and regions. https://www.iea.org/countries (accessed on 20.09.2020).

IRENA (2020) Renewable Power Generation Costs In 2019.

Marques, J., G. (2018) Renewables in Central Asia. The Business Year.

Nabiyeva, K. (2020) The Weekend Read: Central Asia’s Green Horizons. pv magazine.

Redman, J. (2020) 3 Cents per kWh – Central Asia’s Cheap Electricity Entices Chinese Bitcoin Miners. Bitcoin News. https://news.bitcoin.com/central-asias-cheap-electricity-chinese-bitcoin-miners/ (accessed on 20.09.2020).

REN21 Secretariat (2020). Renewables 2020 Global Status Report.

Solargis (2020) Solar Resource Map. World Bank Group.

The Economist (2020) America’s domination of oil and gas will not cow China.