By Berdymyrat Ovezmyradov

During my secondments within Central Asian Law project, I had chance to conduct interdisciplinary studies in the field of foreign investments. Being a researcher in supply chain management, I already had a prior knowledge about global value chains related to foreign investments. Still, the conditions and networking provided by the project allowed greatly expanding the knowledge of the investments with regional focus. This article summarizes my analysis of foreign direct investments, hereinafter FDI, which were reflected in Ovezmyradov and Kepbanov (2021).

Do foreign investments really benefit the local population in the end? To what extent did they make ordinary people richer? How to make sure the investments actually have a better impact on wellbeing in the future? Can foreign investors contribute to improving the dire situation with human rights and freedom? Governments and businesses often like to paint a rather rosy picture of FDI benefits. Therefore, I became interested in answers to the above questions in the context of Central Asian countries. There is no big shortage of literature on foreign investment in the region but few papers focused on the problem of long-term benefits of FDI as of 2020s.

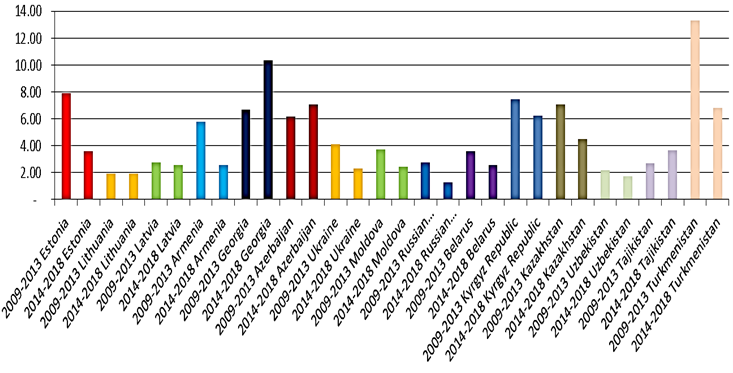

As I reviewed the scientific literature and empirical evidence, my views on the investments became increasingly pessimistic, which could seem unwarranted when considering historical data. Countries in Central Asia have long declared welcoming foreign businesses and technology. Capital inflows as a share of GDP in Central Asia was higher than average worldwide for developing countries (Bayulgen 2005). Cheap and abundant electricity, workforce, and resources in the region attract interest from foreign businesses (OECD 2019). Most recently, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, the biggest economies in the region, provided favorable conditions for the setup of a business even compared within the Eastern Europe (Santander 2021, US Department of States 2020). Foreign investments as a share of GDP overall declined after 2010, though the same trend was observed in other post-Soviet countries (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 FDI inflows in post-Soviet countries as the average of GDP percentage for two periods: 2009-2013 and 2014-2018 (The World Bank 2020).

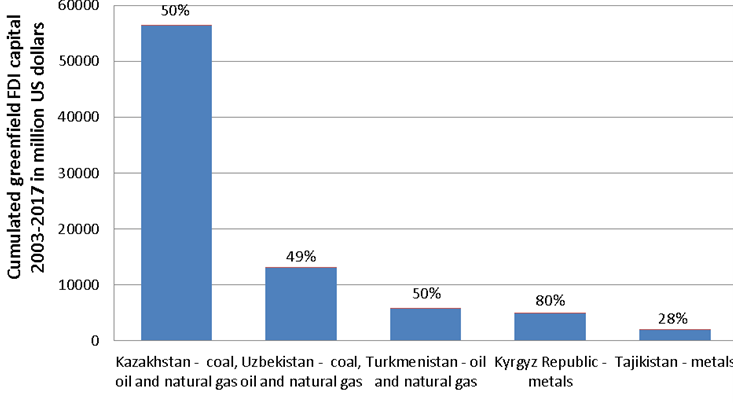

The reason behind pessimism about future investments is not only about the relative decrease – the heavy dependence on extractive industries is even more worrying. Theory says that resource-seeking FDI often harms the local environment in a recipient country and might damage the development prospects in the long run (Moid 2018). With few exceptions among the largest foreign investors (notably, higher interest among businesses from Turkey towards the sectors outside extractive industries, such as textiles, food, and retail), majority of them, unfortunately, were only interested in natural resources. Figure 2 shows how fossil fuel sectors attracted nearly half of the greenfield investments in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Meanwhile, Kyrgyzstan was heavily dependent on metal sector attracting about 80 percent of the foreign investment, while in Tajikistan metals attracted 30 percent. Extractive industries had an outsized role in investments for all of the Central Asian countries. With volatile prices and global demand for commodities, the exports of natural resources might suddenly decrease, especially for oil producers suffering from price wars and relentless expansion of renewable energy (UNCTAD 2020). The extant literature (on the resource curse in particular) suggests natural resource abundance in most countries is associated with reduced economic growth, low democracy levels, and risk of conflicts (Rosser 2006).

FIGURE 2 Cumulated greenfield FDI capital share in extractive sectors 2003 and 2017 (estimated values based on UNCTAD 2021 and OECD 2019 data).

Aside from FDI structure and decrease, another big challenge for Central Asia is to attract more beneficial foreign investments that align with national development, moving to higher-value-added levels with transfer of technology and know-how in agriculture, manufacturing, and services. A final product can be manufactured and assembled in multiple countries, with each step in the process adding value to the end product (World Bank Group 2023). The international transfer of knowledge in global value chains (GVC) determines growth in productivity, employment, and technology. Globalization since the early 1980s led to wider outsourcing and offshoring by companies from the Western countries. China is a prominent example of a developing country that benefitted from the GVC. Current GVC trends might appear as an opportunity to shift a higher share of global production from China to Central Asia, as it happened in neighbouring countries such as Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Thailand, and Malaysia. A neighbouring region did much better: Southeast Asia achieved much higher combined integration to GVC and regional value chains by 2015 despite being similar to Central Asia in 2000. Income growth in Caucasus and Central Asia rates would be 0.7 percent higher if they could enhance their GVC participation – this is higher than from diversifying economies and improving product quality (Kunzel et al 2018). Unfortunately, integration of Central Asia to the global and regional value chains was limited due to inadequate policies, infrastructure, and logistics (Sharafeyeva 2022). The GVC participation of Central Asia globally was the second lowest (Urata and Baek 2020). Corresponding indices for Kyrgyzstan (0.05), Uzbekistan (0.01), Tajikistan (0.03), and Kazakhstan (0.02) were below the worldwide average index of 0.05.

Given the most recent “de-globalization” trend, Central Asia will face even greater difficulties benefitting from the global production specialization and the labor division than many other developing countries competing for foreign investment. The reasons are high logistics cost in the landlocked countries, insufficient human capital, slow liberalization, relatively small population and their income, meaning lower market size and economies of scale relative to alternative locations in Asia. Cheap energy and workforce alone, without other comparative advantages, are not enough to compensate for the above disadvantages. Highly desirable technology transfer from foreign investors in automotive, machinery, and electronics has not been particularly: visible in the region. The prevailing GVC conditions in 2020s for Central Asia appear likely to cause further lowering the level of participation in the near future, not upgrade: reshoring and diversification limit possibilities to benefit from FDI in the medium-low technology intensity (textiles), regional processing (food and chemicals), extractive, and agro-based (James et al 2020). Foreign investments are not very beneficial when domestic organizations with backward technologies and low-skilled labor prevent effective transfer of technology and knowledge. Central Asian countries still lagged behind peers of comparable size in the post-Soviet area in many essential indicators of research and education (Ovezmyradov and Kepbanov 2021, Sanghera and Satybaldieva 2018). As for the not so distant future after 2030, Central Asia is among the regions expected to experience a substantial reduction in GVC participation relative to the period before CoVID-19 pandemic. Climate mitigation policies in the developed countries and other major trading partners, such as the EU Green Deal, will have mostly negative implications for the key sectors of hydrocarbon and mineral extraction in Central Asia (Paul et al 2022.).

While foreign investments might benefit income levels of ordinary people under certain conditions, they seldom promote freedom in any way. In theory, foreign capital might be interested in helping to reduce the costs of doing business by promoting pluralism, the rule of law, and limits of authoritarian tendencies (Bayulgen 2005). In particular, foreign portfolio investment (FPI) can be more effective in promoting institutional reforms in recipient countries than official development assistance (ODA) and FDI. In practice, foreign businesses are naturally interested in the interpretation of rule of law effectively turning to the rule of dispute courts that make it difficult for the public to hold foreign investors accountable for the ecological and social issues, and there are relevant cases in Central Asia (Sanghera and Satybaldieva 2018). FDI and foreign aid often fail to promote political freedoms, when investors prefer dealing with strongmen for “one-stop shopping” in to get an approval rather than negotiating with strong institutions requiring high standards of social responsibility (Bayulgen 2005). Natural-resource rents from extraction of natural resources might accrue to governments and foreign firms in ‘rentier states’ with unfair income distribution, high corruption, and threats to democracy (Sanghera and Satybaldieva 2018). Authoritarian rulers simply ignored international promotion of liberalization since any loans or foreign aid that could be linked to providing more political freedoms were not significant compared to investment inflows in extractive industries (Bayulgen 2005). Even if FDI ensures technology transfer and growth, it does not necessarily bring good governance.

Relationships between rule of law, liberalization and foreign investment look uncertain indeed. For instance, the FDI as share of GDP declined in democratic Estonia and Armenia but increased in authoritarian Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, while the least liberalized Turkmenistan achieved the highest ratios in the comparisons (Figure 1). Kyrgyzstan, a relatively more open economy but less stable politically, had a good FDI/GDP ratio levels but still attracted lower investments than authoritarian neighbours in the region. The differences among Central Asian economies in the capital flows partially explain why some states became illiberal while others remained in hard authoritarianism (Bayulgen 2005). There is little to boast about the growth primarily achieved on account of extractive industries doing little for development directly benefitting the entire society. Liberal post-communist democracies might attract relatively lower foreign investment than authoritarian peers but are more likely to create conditions for their citizens to benefit from such investments in the long run with stronger human capital and the rule of law and political freedom.

Central Asian countries did not have to focus on improving institutions when benefiting from booming revenues due to hydrocarbon and other resources (Billmeier and Massa 2007). Western support of democratic transition in the region emphasized technical measures facilitating economic aspects, while few political and institutional objectives were truly achieved (MacFarlane 2002). Meanwhile, Central Asia depended on external capital empowering authoritarian governments but providing less financial benefits to smaller local businesses (Bayulgen 2005). Compared to success in other post-communist states, the EU demonstrated fewer achievements in promoting the rule of law, human rights, and democratization among Central Asian partners (MacFarlane 2002). In terms of the total FDI stock among the countries of investors’ origin, the EU (42%) and the US (14%) were the main investment partner of Central Asia, far ahead of Russia (6%) and China (4%), even if perception might suggest otherwise (Borrell 2022). Investments originating from Belt and Road Initiative and other sources from China cause higher debt burden, for instance, and do not seem to bring once highly anticipated benefits for Central Asian economies. Political freedoms and human rights never seemed to be prioritized by the Western investors, let alone other players with geopolitical influence in the region. As of 2020s, the final benefit of the foreign investment on sustainable development in Central Asia appears questionable with the slowdown of progress in liberalization and worsening situation with freedom in the region.

Coming back to questions raised at the beginning, I can now summarize doubts about the investment benefits for Central Asia in the long run.

Do foreign investments make the people better off economically? Not very much. The concentration on extraction of natural resources and disadvantaged position in the global value chains do not allow gaining the full benefit. Even though the region attracted relatively high foreign direct investments in the first three decades after gaining independence, the ongoing changes in the global demand for commodities together with the reconfiguration of supply chains mean the contribution of investment in economic growth will be hard to maintain with the current characteristics of extractive sectors and human capital. The investment structure just does not strongly support technology transfer and shift to knowledge economy.

Do foreign investors somehow promote protection of human rights and freedom? The answer is negative. Numerous indicators of development indicate the population has long suffered from the lack of good governance, on average, more than other post-Soviet regions. Unfortunately, the starting conditions of foreign investment appear far from bringing a stronger rule of law and political freedoms in Central Asia. If potential for environmental damage and corruption risks from investments is considered, their benefits in the region could be further questioned.

To summarize, the negative effects of foreign investments on sustainable development of Central Asian countries sadly might exceed their short-term benefits.

Keywords: Central Asia, transition economies, foreign investment, sustainable development.

References

A. Billmeier and I. Massa, What Drives Stock Market Development in the Middle East and Central Asia – Institutions, Remittances, Or Natural Resources? (2007).

A. Rosser, The political economy of the resource curse: A literature survey (Vol. 268). Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex (2006).

B. Sanghera, E. Satybaldieva, Rentier Capitalism and Its Discontents. Springer International Publishing (2021).

B. Ovezmyradov, Y. Kepbanov, Comparative Analysis of Higher Education And Research In Central Asia From The Perspective Of Internationalization. Central Asian Law: Legal Cultures, Governance And Business Environment In Central Asia, 25 (2020).

B. Ovezmyradov, Y. Kepbanov, Human capital and liberalization in Central Asia: comparative perspectives on development (1991 – 2020). Lund University (2021).

A. Sharafeyeva, How much do Central Asian countries participate in regional value chains? Australian and New Zealand Journal of European Studies, 14(2), (2022): 62-80.

J. Borrell, Central Asia’s growing importance globally and for the EU (2022) eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia’s-growing-importance-globally-and-eu_en accessed on July 20, 2023.

O. Bayulgen, Foreign capital in Central Asia and the Caucasus: curse or blessing? Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 38(1) (2005): 49-69.

OECD, Sustainable Infrastructure for Low-Carbon Development in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Hotspot Analysis and Needs Assessment. OECD Library (2019).

M. P. J. Kunzel, De Imus, P., Gemayel, M. E. R., Herrala, R., Kireyev, M. A. P., & Talishli, F. (2018). Opening Up in the Caucasus and Central Asia: Policy Frameworks to Support Regional and Global Integration. International Monetary Fund.

S. Moid, M&A vs. Greenfield: FDI for Economic Growth in Emerging Economies. In Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) and Opportunities for Developing Economies in the World Market (IGI Global 2018): 169-185.

S. N. MacFarlane, Caucasus and Central Asia: towards a non-strategy. Geneva Center for Security Policy (2002).

Santander, Foreign investment. Trade Markets (2021).

S. Urata, Y. Baek, The determinants of participation in global value chains: A cross-country, firm-level analysis (No. 1116). ADBI Working Paper Series (2020).

The World Factbook, Country comparison: stock of direct foreign investment – at home. Library of the Central Intelligence Agency (2020).

UNCTAD, Foreign direct investment: Inward and outward flows and stock, annual. Data Center (2022).

UNCTAD, The World Investment Report 2019. United Nations (2019).

UNCTAD, The World Investment Report 2021. United Nations (2021).

United Nations, Trade and development report 2022 (2022).

US State Department, Investment climate statement: 2020 (2020).

V. Vitalis, Official development assistance and foreign direct investment: improving the synergies (2002).

The World Bank, Statistics (2020).

World Bank Group, Global Value Chains (2023). https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/global-value-chains accessed on March 20, 2021.

World Factbook, Country comparison: stock of direct foreign investment – at home. Library of the Central Intelligence Agency (2020).

WTO, Trade in value-added and global value chains: statistical profiles (2023).