by Carlo Nicoli Aldini (Project Assistant at the Sociology of Law department of Lund University and Guest Researcher at the Academy of the General Prosecutor’s Office of Uzbekistan

I am writing my first blog post from Samarkand. It’s roughly 10 am and Gian Luca and I are having a coffee facing the astonishing beauty of the Registan. Gian Luca is a student at the Master of Sociology of Law, and he is doing his third semester curricular internship at the Academy of the General Prosecutor’s Office of the Republic of Uzbekistan, where I am seconded until December. This morning we woke up at dawn to come see the square under the soft sunrise light, which was a calm, powerful, and reinvigorating experience. It’s our third day in Samarkand and this town has conquered our hearts already.

From the perspective of two Italians doing research in Uzbekistan, this town is fabled and magic, a place we would have rarely imagined travelling to. But Samarkand and Uzbekistan alike are much more than an exotic destination for us: in these initial weeks, they have given us immense resources to think about the theories of the sociology of law that we studied on the books in Lund, Sweden. In this first post, I would like to share a reflection that Gian Luca and I had yesterday after visiting one of Samarkand’s landmark touristic destinations, the Shah-i-Zinda, a necropolis that includes a sequence of breathtakingly beautiful turquoise mausoleums.

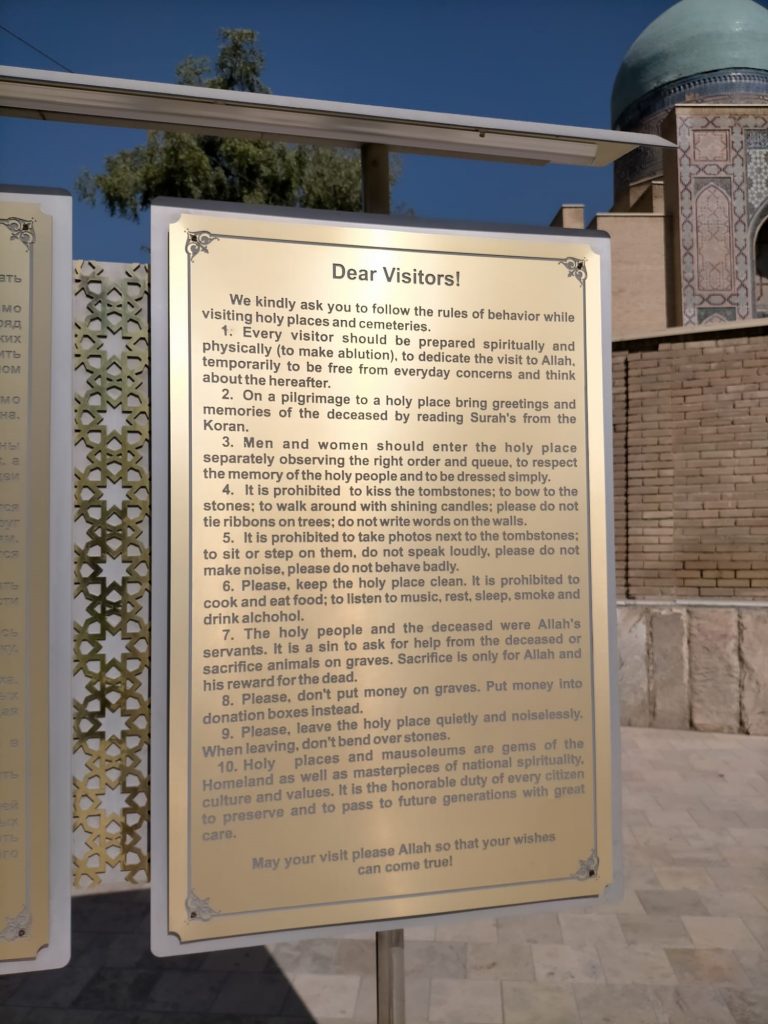

At the entrance of the Shah-i-Zinda, one can find a banner that lists in Uzbek, Russian, and English the rules of behavior that visitors are expected to keep while wondering around the lapis lazuli-colored site. Here’s my picture of the panel:

Let us look at rule n. 8! It clearly states: Please, don’t put money on graves. Put money into donation boxes instead. However, despite the rule’s clarity, we barely found a grave without Uzbek soʻm banknotes on it. This was not a surprise to us: we discovered the same norm of behavior in many other mausoleums we had previously visited along our journey. Yet, this time we immediately noticed the stark contrast with the letter of the “official law” at the site’s gate.

Upon discussing the evident discrepancy between what the authority expects people to do, and how people really behave, Gian Luca and I agreed that there is one question that is essential to answer in order to comprehend the behavior of the visitors of Shah-i-Zinda: is leaving the money over graves an instance of disobedience (and thus a violation of state law), or is it an example of a different legality that shapes people’s behavior contextually to state law in the same, legally-plural, social arena?

This puzzle is truly a socio-legal one. Conceptually, it is indeed a representation of one of the evergreen debates of the sociology of law, namely the difference between the law-in-action and the living law (see e.g., Nelken 1984; Hertogh 2004). I am aware I cannot answer this question as I have not collected any data beside my observation: in order to provide a “thick description” (Geertz 1973) of what I had observed I would have had to, arguably, interview those visitors who left money over the graves in order to comprehend the reasoning behind their gestures. In socio-legal terms, I would have needed to investigate their legal consciousness.

For now, I am left with the awe of Samarkand’s beauty in my eyes and with the promise that my secondment in Uzbekistan will offer many more occasions to reason over these questions.

References.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation Of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Hertogh, Marc. 2004. A `European’ Conception of Legal Consciousness: Rediscovering Eugen Ehrlich. Journal of Law and Society 31 (4): 457–81.

Nelken, David. 1984. Law in Action or Living Law? Back to the Beginning in Sociology of Law. Legal Studies 4 (2): 157–74.