BY TOLIBJON MUSTAFOEV

(Transparency International, 2021)

In this post, Tolibjon Mustafoev shares his preliminary analysis on critical reflections and methodological considerations of Transparency International’s standardization method for generating the Corruption Perceptions Index. He also discusses the nexus between transparency, indices and business climate in Uzbekistan.

What is Transparency International (TI)? And what does it generate?

TI is recognized as the ‘corruption measuring’ institution which observes and notes the level of corruption in societies worldwide. Since 1995 Transparency International with the Internet Centre for Corruption Research at the University of Passau in Germany has analyzed the level of corruption perception in more than 180 countries around the world. Transparency International focuses on evaluating and systematizing corruption measurement in countries and publishing results annually (CPI); in addition, it also publishes a Global Corruption Barometer, Global Corruption Report, and a Bribe Payers Index.

The Global Corruption Barometer debuted in 2003 and since that year has surveyed the experiences of everyday life of people confronting corruption around the world. Through the Global Corruption Barometer, tens of thousands of people around the globe are asked about their views and experiences, making it the only worldwide public opinion survey on corruption. Furthermore, the Global Corruption Report is Transparency International’s flagship publication, bringing the expertise of the anti-corruption movement to bear on a specific corruption issue or sector. The Global Corruption Report: Education consists of more than 70 articles commissioned from experts in the field of corruption and education, from universities, think tanks, business, civil society and international organizations. One more essential part of Transparency International’s working scope is publishing the Bribe Payers Index which ranks the world’s largest economies according to the perceived likelihood of companies from these countries to pay bribes abroad. It is based on the views of business executives as captured by Transparency International’s Bribe Payers Survey. (Transparency International, 2020)

This Berlin-based NGO got world recognition as one of the most influential ‘corruption measurement’ data publishers; the well-known annual index published by Transparency International is the Corruption Perceptions Index (or CPI). Following index scores and ranks countries/territories based on at what extend the public sector is corrupted. It is a composite index, a combination of 13 surveys and assessments of corruption, collected by a variety of reputable institutions. The CPI is the most widely used indicator of corruption worldwide.

Furthermore, corruption-related ratings and indices, indirectly and directly, affect the foreign direct investment (FDI) and business attractiveness of developing states (Woo & Heo, 2009). Following this further, I am focusing on Uzbekistan in this blog post. The country is gradually adopting a new course to combat corruption crimes and improve its image in international rankings to attract more foreign investments. The adoption of the law of the Republic of Uzbekistan “On Combating Corruption” – № LRU-419 dated January 3, 2017, has become an important factor in combining the efforts and interest of state bodies and civil society institutions for starting joint work in corruption eradication. However, there are still some legal and institutional challenges that are creating obstacles to the effective enforcement of state anti-corruption policies. These obstacles affect Uzbekistan’s positioning in various international ratings including the Corruption Perceptions Index. The following blog critically discusses the nature of the standardization of CPI, ongoing reforms of Uzbekistan and their affiliation with positioning in CPI by applying qualitative methods, specifically, documentary analysis and semi-structured interviews. This blog post is a part of my research conducted between 2019 and 2020 as a visiting research fellow at Lund University within the Central Asian Law Project (no 870647) supported by a Marie Curie Research and Innovation Staff exchange scheme within the H2020 Programme.

Respondents representing foreign companies within my research shared their step-by-step experience of investing and starting their business operations in Uzbekistan. One of their first steps was reading and analyzing reports on transparency and governance in Uzbekistan. The Corruption Perceptions Index was the most popular document to rely on for the majority of my respondents. Complex area coverage and comprehensive methodology make the CPI one of the most popular rankings considered by foreign businesses before investing in Central Asian market.

The blog post is divided into three parts. The first part describes the methodological challenges of the Corruption Perceptions Index and critically investigates the effectiveness of the standardization method applied by Transparency International to generate its indices. The second narrative is focused on Uzbekistan and how this country has been evaluated by Transparency International for the last few years. And the last part of the blog provides a broader understanding of the legal cultures, accountability in the public sector, and democratic processes within the context of transparency phenomena; and this debate is linked to the positioning of Uzbekistan in the CPI. Thus, the following blog post raises awareness about the importance of considering the need to rethink the policies of countries that regard international indices as an important factor to economic growth and correspondingly make decisions that indirectly initiate a race in indices such as the CPI.

Ratings by TI: methodological challenges of corruption measurement

The international ratings by Transparency International, Freedom House, World Bank, Bertelsmann Foundation, and World Economic Forum measure the level of corruption perception and transparency in different public and private sectors by applying the standardization method. Standardizing expresses comparing different values by normalizing and bringing them back to a single scale. In the case of the CPI, all values of the sources are brought to a single scale expressed from 0 to 100; where 100 is less perception of corruption, and 0 is the highest indicator of the corruption propensity. According to Transparency International experts, the standardization method allows for identifying the most corrupt areas of public administration and institutions. However, several legal scholars believe that ratings do not illustrate the measurement of “corruption”, but just standardize people’s thoughts and perceptions about corruption. Tina Søreide challenges the nature, effectiveness, and reliability of Transparency International’s CPI. She claims that the CPI is not based on “true facts about the actual levels of corruption”; rather, she calls it an “index of indices’’ (Søreide, 2006). Despite this, Corruption Perceptions Index by TI remains the most applicable and popular index regardless of the existence of scholarly arguments which claim that CPI is politicized and it applies the unjustified and unpractical methodology of standardization.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index is recognized as a “first-generation index” that applies diverse instrumental and statistical techniques to measure corruption by its perception in society (Johnston, 2000). These diverse statistical and data analysis techniques guarantee the CPI its leading position among the world’s corruption evaluation and analytical observation indices. However, some legal scholars argue about the validity of Transparency International’s corruption perception methodology. According to Bevan and Hood (2006, p.517), any complex governance system needs a special form of control that relies on measured performance indicators and administration by targets (Bevan & Hood, 2006). The absence of the exact “measurement” formula for evaluating the level of corruption challenges the comprehensiveness of the methodology applied by TI for making its reports and indices. Most of the sub-indicators of the CPI sources concentrate on the level of public management issues, transparency in public-sector activities, effective governance, and tolerance for corruption. The complexity and variety of sources applied by TI for creating the CPI make the corruption measurement process difficult, or even unclear.

The CPI is a score-registering trend that raises awareness about ongoing corruption-related scandals. It has a unique character, which is very influential in world politics and image-making but is not practical for countries. For example, Transparency International’s reports and indices cover only the problems, but not the solutions. Because of the standardization method, countries struggle to raise their positions in the CPI in order to improve their business and investment attractiveness. Any government reforms or sustainable development that includes anti-corruption efforts cannot guarantee an improvement of the position of the state in the CPI. Even though Transparency International standardizes countries according to its own methods, it does not and cannot provide any practical recommendations or advice for governments on the possible ways to improve their scores and position on the CPI or to better their high-risk, corruption-prone public sectors. Consequently, Gultung also agrees that theCPI mostly criticizes because it does not provide any solutions or answers to the existing corruption-related problems. Indeed, it is more practical to identify the solutions rather than raise awareness about the problems. Galtung claims that“giving harsh and negative scores to countries where reformers are hard at work is to denigrate their work and to feed cynicism and the belief that whatever they are trying to do will be unsuccessful”. Thus, countries consider the CPI to be a race to the top, but in reality, it is the opposite (Governance-Access-Learning Network, 2014).

Uzbekistan in the CPI: validity and reliability of applied data by TI

Despite critiques of Transparency International’s methodology, Uzbekistan strives to improve its position on the CPI. But the standardization method tracking the progress of all countries is such that simultaneous progress in the anti-corruption sector in several developing countries can still influence the position of Uzbekistan on the index. Thus, getting high positions in the CPI is quite challenging regardless of the progress made by a state over a short period because of the subjectivity of progress analyzes and the standardization method.

The first data about Uzbekistan in the Corruption Perceptions Index was published in 1999 and was based on surveys from four sources. In some years, the country was leading the Central Asian region in the Index. But Uzbekistan started getting low scores and correspondingly lower positions on the CPI due to the enlargement of the number of surveys and sources. In 2014, the country scored 18 out of 100 on the scaled computing system. This score ensured Uzbekistan would rank 166th among 175 countries, meaning it was recognized as the Central Asian country with the second-highest level of corruption perception and corrupt public sector after Turkmenistan, which received 17 points in 2014. The most important data that TI relied upon to measure the level of corruption perception in Uzbekistan in 2014 was presented by the World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators, where the country performed poorly on all six of the main dimensions of governance assessed, which were:

- Voice and accountability

- Political stability and absence of violence

- Government effectiveness

- Regulatory quality

- Rule of law

- Control of corruption (Martini, 2015)

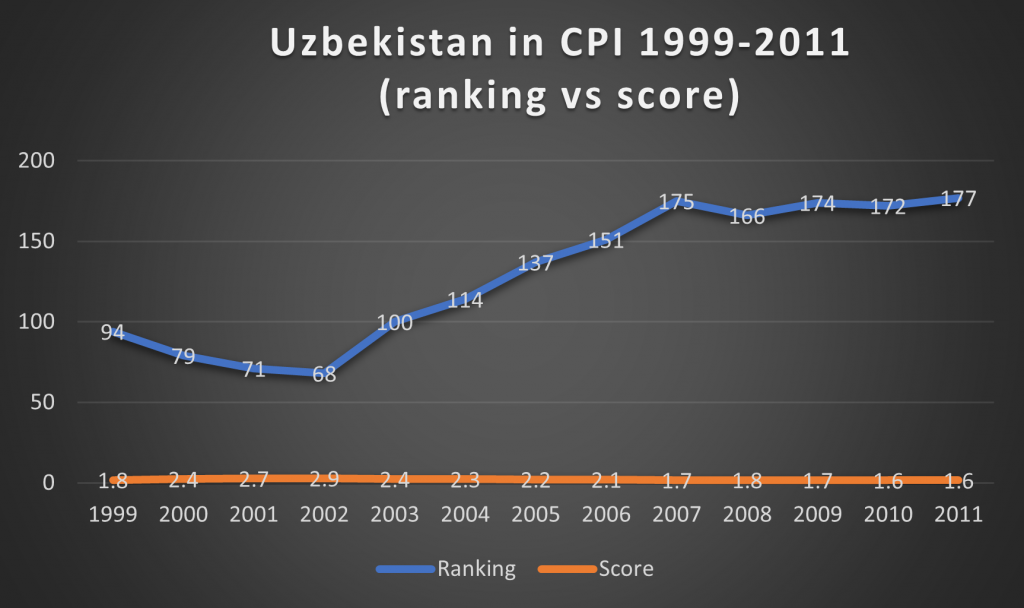

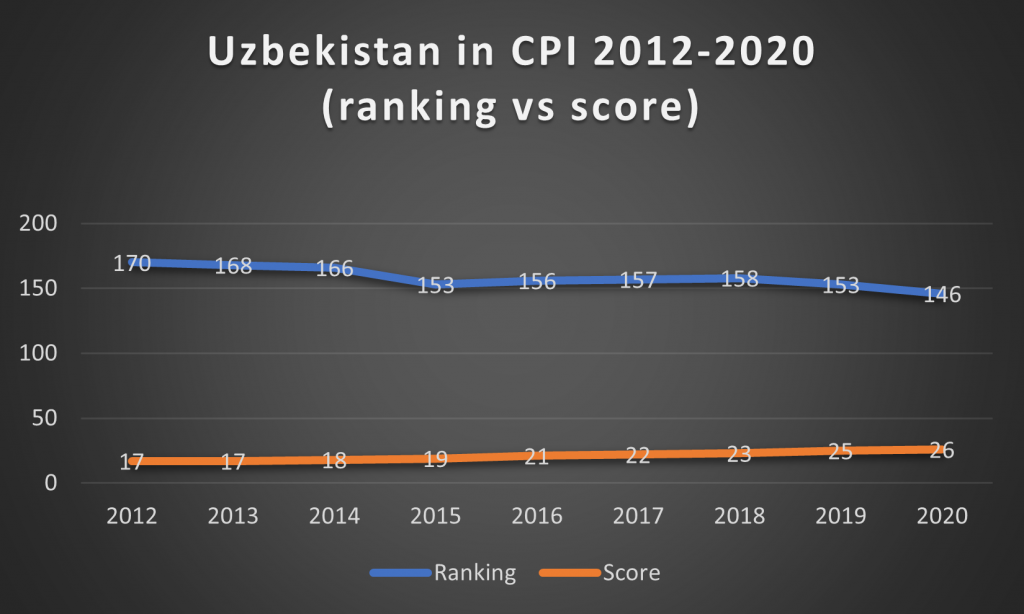

Transparency International’s standardization method’s progression applied by the CPI for Uzbekistan consists of two periods: 1999-2011 (with the maximum score of the index of 10) and 2012 – 2020 (with the maximum score of the index 0f 100). Both periods illustrated in the following graphs:

- The first period as following:

Ranking: 1 (least corrupt) – 182 (most corrupt)

Score: 0 (highly corrupt)- 10 (very clean)

| Year | Ranking | Score |

| 1999 | 94 | 1.8 |

| 2000 | 79 | 2.4 |

| 2001 | 71 | 2.7 |

| 2002 | 68 | 2.9 |

| 2003 | 100 | 2.4 |

| 2004 | 114 | 2.3 |

| 2005 | 137 | 2.2 |

| 2006 | 151 | 2.1 |

| 2007 | 175 | 1.7 |

| 2008 | 166 | 1.8 |

| 2009 | 174 | 1.7 |

| 2010 | 172 | 1.6 |

| 2011 | 177 | 1.6 |

(b)The second period as following

Ranking: 1 (least corrupt) – 198 (most corrupt)

Score: 0 (highly corrupt)- 100 (very clean)

| Year | Ranking | Score |

| 2012 | 170 | 17 |

| 2013 | 168 | 17 |

| 2014 | 166 | 18 |

| 2015 | 153 | 19 |

| 2016 | 156 | 21 |

| 2017 | 157 | 22 |

| 2018 | 158 | 23 |

| 2019 | 153 | 25 |

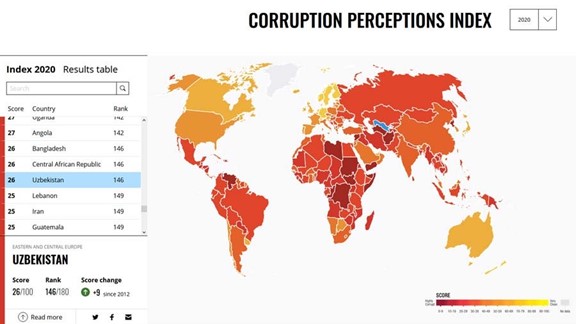

| 2020 | 146 | 26 |

The score for Uzbekistan in 2018 took into account data from such sources as:

- Bertelsmann Foundation Transformation Index (Uzbekistan – 21)

- Economist Intelligence Unit Country rating (Uzbekistan – 20)

- Freedom House Nations in Transit Rating (Uzbekistan – 21)

- Country risk rating – Global Insight (Uzbekistan – 22)

- CPIA – World Bank (Uzbekistan – 18)

- Rule of Law Index – World Justice Project (Uzbekistan – 34)

- Annual report on democracy – project “Diversity of democracy” -V-Dem. (Uzbekistan – 23)

Eastern Europe and Central Asia including Uzbekistan are recognized by Transparency International as the second-lowest performing region, where the average score is 35 (Transparency International, 2019). Currently, Uzbekistan with its 20 points is the 146 least corrupt out of 180 countries, according to the 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index reported by Transparency International. In comparison to 2019, Uzbekistan has enhanced its positioning by 7 ranks.

The recent years the standardization method applied by Transparency International recalculates the original scores and standardizes them according to a scale from 0 as the most corrupt to 100 as the least. The aforementioned dimensions of governance used by TI analyze almost all of the political and social aspects, reforms, challenges, rule of law, and economic stability of the state. The methodology used by all sources varies from one to another but the assessment process remains comprehensive and “large scale.” Apart from this, the Bertelsmann Foundation critically discusses the conflicts of interest in the public sector, which can create extra motives for further corruption schemes. Experts from the Bertelsmann Foundation (BF) mostly referred to the intersection of interests in the public and private sectors. Mostly, they gathered information from open sources and referred to the survey results that aim to collect data from individual experts or private-sector representatives. For example, the latest report of the BF mentions the following:

…unfortunately, the government does not use transparent and non-discriminatory criteria in evaluating requests for permits to associate and/or assemble. More often than not, groups are not able to operate free from unwarranted state intrusion or interference in their affairs. For example, the government adopted a rule in 2013 that NGOs receiving grants from international organizations or foundations must open a special bank account for those grants and a special commission must issue permission for the use of the grant. Such a measure was established as means to control NGO activities (Bertelsmann Foundation, 2018).

The Bertelsmann Transformation Index country report on Uzbekistan for 2020 highlights several times that the analyzed data is mostly taken from official state sources (Official websites and reports of Uzbekistan’s Government, the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook), which means the, at least in this report, experts have referred to the most valuable and accountable data available.

Transparency International mostly evaluates institutional and legal anti-corruption frameworks; in addition, it critically evaluates the high-corruption-risk public sectors of Uzbekistan such as healthcare, police, security and defense, education, public administration, and agriculture. Different international indices including the CPI always try to stay “objective” during the data collection, analyzing and ranking processes. The affiliation level of the legal and institutional anti-corruption reforms of any state with its positioning in the Corruption Perceptions Index depends on data from three main sources that are recognized as corruption indicators (Fakezas, Toth & King, 2016):

- Different types of surveys related to the perception of corruption and the most widely held attitudes.

- A critical review of the state efforts in anti-corruption policy and its existing legal and institutional frameworks.

- A detailed version of the analyses and audits of individual cases.

The CPI, in particular, considers a very large scale of corruption “measurement”. Public policy, recent updates, and existing challenges in public-sector business dealings mostly affect state positioning on the CPI. Moreover, the report of the 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index highlights the main directions of the public sector in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) that are strongly linked to the final results or ranking. The CPI in its report on the Central Asian countries highlights that “across the region, countries experience a limited separation of powers, abuse of state resources for electoral purposes, opaque political party financing and conflicts of interest” (Transparency International, 2020). Moreover, the report states that “strong political influence over oversight institutions, insufficient judicial independence and limited press freedoms serve to create an over-concentration of power in many countries across the region”(Transparency International, 2020).

The nexus among transparency, accountability and the CPI

Transparency can make state workers more responsible in informing people about the thousands of tasks that they carry out and constantly letting them know about the status of implementation. All governments can issue hundreds of new regulations, but the most important part is implementation and control; thus, transparency could assure this. Issues of corruption and the failure to provide transparency can be seen as symptoms of a larger problem. Confidence of both government and citizens in political processes is considered to be the main imperative for the enhancement of transparency and democracy in the state. Holding government officials accountable for the decisions made by them and their actions can be reached only by providing greater transparency and openness in the public sector (Kierkegaard, 2009). In this regard, democratic processes are successful only when the government ensures transparency in its public sector and allows all citizens to actively participate in the decision-making process on policies or laws that have a direct effect on peoples’ everyday routines and lives. Considering this further, Ball claims thatonly “when citizens have information, governance improves. Transparency occurs through the support of society, government, media, and business for open decision-making” (Ball, 2009).Thereby, the important aspects of transparency in the public sector are letting people track and monitor government actions and ensuring direct public control over state policy implementation processes. Direct public control within the context of transparency means the direct participation of citizens in the policy decision-making and implementation process rather than an indirect monitor through representatives where the results only arise from democratic values (Meijer, 2013).

Uzbekistan has taken steps to actively encourage citizens and people living in the country to participate in discussions of state projects, amendments to existing legal acts, and norms. However, these initiatives should be filled in by implementing more effective “feedback” mechanisms which will account for the views of various civil society institutions and actors. For example, before conducting a general review of legal acts, the Ministry of Justice takes into consideration people’s comments on those acts and policy initiatives that are normally published in the regulations.go.uz portal. Ensuring people’s participation in discussions is a very positive experience within the scale of transparency, but it needs to be enhanced in terms of raising public awareness about this portal and ensuring the reporting by the government about the progress and results of implemented projects, policies, or laws.

Transparency and accountability in the public sector are powerful allies in any anti-corruption policy. Previously discussed practices of foreign countries with better positions on the CPI show that Uzbekistan can get better world recognition for its anti-corruption efforts by internationalizing the values aligned with citizenship and government that should be open and transparent. All these recommendations highlight the importance of people’s feeling as participants in political processes, not just as observers, but“also for the rescue of ethical values by politicians and public officials in order to generate greater confidence in the government” (Lyrio, Lunkes & Taliani, 2018). As a matter of fact, getting high ranks and better positions on the international indices on transparency and governance, including the Corruption Perceptions Index, depends on minimizing corruption problems and cases, enhancing social welfare, strengthening democracy, applying participatory prac tice and providing sufficient access to information and following accountability governance principles.

Following the previously made analyses about providing sufficient access to information regarding public-sector dealings and relying on the nineteenth recommendation of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) country progress update within the third round of monitoring under the Istanbul Anti-corruption Action Plan, Uzbekistan needs to “ensure that legislation on free access to information limits discretion of officials in refusing to provide information; set precise definitions of the ‘state secret’ or other secret protected by the law; carry out campaigns to raise citizens’ awareness about their rights and responsibilities in regard to the access to information regulations. Ensure systematic training of officers who are responsible to provide information on the access to information” (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2015).

Even with the existence of a legal framework that guarantees people’s right to access to information related to the public sector, it is not practical if people’s awareness of this is low. Therefore, providing official and accountable information to the public leads to an increase of trust in the government and a possible decrease in the social phenomenon oflegal corruption. The accuracy, appropriateness, and up-to-datedness of the published information are very important to gain public trust and ensure transparent business performance in the public sector.

Concluding remarks

In this blog, I provided a critical and descriptive analysis of Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and it’s widely used standardization method. The CPI is one of the leading corruption perception ratings in the world which shapes the business and investment attractivity of the evaluated countries within this index. The investment climate and business environment in Central Asia are shaped by the CPI at a certain point, because foreign businesses need accurate and reliable information about the region before initiating any projects and so that they approach the CPI. In fact, most of the Central Asian countries have low positioning in the CPI and it might be influenced not only by the issues related to liberalization policies or democratic challenges but also with informal legal cultures in society and high level of inter-personal networks.

Despite the critics of the methodology, the CPI remains an actively applicable index by businesses to be applied before investing in the new destinations. Countries with developing economies, like Uzbekistan, are racing in the CPI to get better scores within their regions and attract more businesses and financial flows. However, the standardization method of the CPI is making this race to the bottom, not to the top.

Bibliography

Ball, C. (2009). What is transparency? Public Integrity, 11(4), 293–308. doi:10.2753/PIN1099-9922110400

Bertelsmann Foundation. Transformation Index BTI 2018 Country Report- Uzbekistan. – 2019. [online resource]URL:btiproject.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2018/pdf/BTI_2018_Uzbekistan.pdf

Bevan, G., & Hood, C. (2006). “What’s measured is what matters: targets and gaming in the

English public health care system”, Public Administration, Vol. 84 No. 3., 517-538.

European Commission Internal Market and Services. (2011). EU public procurement legislation: delivering results Summary of evaluation report. [online resource] URL: file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/executive-summary_en.pdf

Fakezas, M., Toth, I., & King L. (2016). ‘An Objective Risk Index Using Public Procurement Data’, European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (3), 368-370 . [online resource] URL: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301646354_An_Objective_Corruption_Risk_Index_Using_Public_Procurement_Data

Galtung, F. (2008). “Measuring the immeasurable: boundaries and functions of (macro)

corruption”, in Sampford / eds C., Shacklock, A., Connors, C. and Galtung, F., – Measuring Corruption, – Ashgate: Aldershot, 101-30.

Johnston, M. (2000). The New Corruption Rankings: Implications For Analysis And Reform (Department of Political Science Colgate University). [online resource] URL: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228848458_The_New_Corruption_Rankings_Implications_for_Analysis_and_Reform>

Kierkegaard, S. (2009). Open access to public documents—More secrecy, less transparency! Computer Law and Security Review, 25(1), 3–27. doi:10.1016/j.clsr.2008.12.001

Law of the Republic of Uzbekistan “On Combating Corruption” dated January 3, 2017., № LRU-419 [online resource] URL: https://lex.uz/docs/4056495 (Accessed 20 January 2020)

Lyrio M., Lunkes R., & Taliani E. (2018) ‘Thirty Years of Studies on Transparency, Accountability, and Corruption in Public Sector: The State of the Art and Opportunities For the Future Research’, Public Integrity 20 (5), 525-527

Martini, M. (2005). Transparency International// Overview of corruption and anti-corruption: Uzbekistan. [online resource] URL: https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/helpdesk/overview-of-corruption-and-anti-corruption-uzbekistan

Meijer, A. J. (2013). Understanding the complex dynamics of transparency. Public Administration Review, 73(3), 429–439. doi:10.1111/puar.12032

Søreide, T. B. (2006). Is it Wrong to Rank? A Critical Assessment of Corruption Indices, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2006: 1) , 13-14.

The Governance-Access-Learning Network , The Galtung Critique of the Corruption Perceptions Index of Transparency International, Interview notes dated 14 October 2004.

Transparency International. (2019). Report on corruption Perceptions Index 2019. https://www.transparency.org/cpi2019

Transparency International. (2020). Report on corruption Perceptions Index 2020. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/nzl

Woo, J., & Heo, Uk. (2009). Corruption and Foreign Direct Investment Attractiveness in Asia. Asian Politics & Policy. 1. 223 – 238. 10.1111/j.1943-0787.2009.01113.x

World Bank. (2017). Improvement of the Public Procurement System in the Republic of Uzbekistan. [online resource] URL: http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/816741495971667917/Uzbekistan-13th-PEIMO-Forum.pdf